The Author Interviewed

The following article by Jennifer Gall, Visiting Fellow, ANU School of Music, formed the basis of her article “Shining a light on Wagner” which appeared in The Canberra Times’s Panorama on Saturday, 19 May 2012.

In an age when some publishers are compromising on both editorial diligence and production values, it is a pleasure to discover Great Wagner Conductors written by Canberra-based author Jonathan Brown. The 800 page illustrated tome is a rigorous, erudite examination of its topic based on analyses of historical performances, recordings and reviews relating to the selected conductors. The book builds on Brown’s earlier critical discographies: Parsifal on Record (Greenwood, 1992) and Tristan and Isolde on Record (Greenwood, 2000). The latter volume won the prestigious international Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC) 2001 Award for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research (Classical Music). In an interview with Brown, I asked the author to explain why he had embarked on the Wagner project.

Canberra is the perfect place to research and write a book about great Wagner conductors, Brown believes. Because the city does not possess an opera house, anyone who is interested in Wagner is bound to turn to recorded music, of which there is much. Motivation to embark on research for the current book evolved over time:

“For many years I’ve listened to Wagner’s music and I had a growing concern that the exciting recordings I’d heard weren’t acknowledged in the general understanding of the great Wagner conductors. There was a disparity between what biographers said about conductors and what I heard with my own ears. So when the fertile fields of retirement opened I decided I would travel to archives and libraries in cities around the world where these conductors performed, read reviews of their actual performances and compare these against the recordings that they left. I was very pleased to see, in some cases, that the conductors that had struck me as being exciting had also been regarded as exciting by the reviewers of their performances. Similarly, with some conductors who had been very highly regarded and promoted by the record industry about whom I had doubts, I discovered that reviewers of their performances also had misgivings - and I thought that this was a story. Here was an injustice that had to be corrected or uncovered. It was worth writing a book.”

Why choose conductors and not singers as the lens through which to examine Wagner’s music historically? Brown answers: "Because so much depends on the conductor, as Wagner himself wrote. In some cases this is everything." A whole performance depends upon the conductor who will use the flexibility of Wagner’s score to support the singers and guide the audience to the meaning at the heart of his monumental operas. “A good analogy is that of the stained glass window. Often you can’t see the detail, but occasionally the sun appears behind it and illuminates all that is really there. And that is true of a great Wagner conductor. Wagner’s music conducted by anyone sounds O.K., then suddenly a great personality enters behind it in the form of the conductor, and we think “Ah! That’s what it’s all about!”

Why choose conductors and not singers as the lens through which to examine Wagner’s music historically? Brown answers: "Because so much depends on the conductor, as Wagner himself wrote. In some cases this is everything." A whole performance depends upon the conductor who will use the flexibility of Wagner’s score to support the singers and guide the audience to the meaning at the heart of his monumental operas. “A good analogy is that of the stained glass window. Often you can’t see the detail, but occasionally the sun appears behind it and illuminates all that is really there. And that is true of a great Wagner conductor. Wagner’s music conducted by anyone sounds O.K., then suddenly a great personality enters behind it in the form of the conductor, and we think “Ah! That’s what it’s all about!”

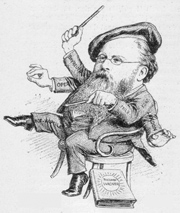

Great Wagner Conductors took five years to research and write, with an extra year for publication. Brown did a lot of listening in Canberra and in archives overseas to test his hypothesis that conductors who were promoted ferociously were not necessarily in the same class as others with a lesser media profile. Brown made three world trips, visiting 11 countries, to search 50 libraries and archives for evidence. He describes his self-imposed high benchmark for the book: “When I found holes in the text I went back overseas to check. I wasn’t going to compromise in any way. So 900 books, many hundreds of listening hours and thousands of reviews had to be condensed into about 30 pages per conductor, which took judicious selection. I made each chapter as interesting as possible with anecdotes and illustrations of conductors in action. It was a joy to sift through archival picture files. Many images have never been published before and I believe that unique illustrations interwoven with the text are essential to ensure the readability of the book.

The prime discoveries were two conductors who have been unjustly overlooked in the record of Wagner’s conductors. Brown found Artur Bodanzky (1877-1939), an Austrian pupil of Mahler’s who conducted at the Metropolitan Opera from 1914 to his death in relative obscurity in 1939. A great range of critics remarked how strongly reminiscent of Mahler his conducting was with an intensely dramatic style and the ability to create endless variation in his performances. The surviving sound recordings are the proof of his talent. He was induced to cut his operas by management and the New York public and he was criticised for this. “When you listen to Bodanzky’s live broadcast recordings they are intensely dramatic unlike studio recordings of the era. He conducts Götterdammerung as if it really is the end of the world with the Rhine overflowing, inundating all life – it’s tremendous! And he just races through it in comparison with modern versions that spread the music out and lose the dramatic fervour.”

The prime discoveries were two conductors who have been unjustly overlooked in the record of Wagner’s conductors. Brown found Artur Bodanzky (1877-1939), an Austrian pupil of Mahler’s who conducted at the Metropolitan Opera from 1914 to his death in relative obscurity in 1939. A great range of critics remarked how strongly reminiscent of Mahler his conducting was with an intensely dramatic style and the ability to create endless variation in his performances. The surviving sound recordings are the proof of his talent. He was induced to cut his operas by management and the New York public and he was criticised for this. “When you listen to Bodanzky’s live broadcast recordings they are intensely dramatic unlike studio recordings of the era. He conducts Götterdammerung as if it really is the end of the world with the Rhine overflowing, inundating all life – it’s tremendous! And he just races through it in comparison with modern versions that spread the music out and lose the dramatic fervour.”

The other forgotten conductor Brown hopes to have given some historical justice to is the Russian born Englishman, Albert Coates (1882-1953), who was a great favourite of the Tsar. Coates came to England some years after the revolution and he created a sensation at Covent Garden. HMV records recognised his talent. “Only excerpts of his performances were recorded but some of these selections show what a prodigious and volcanic conductor he was. Coates’s volatile personality upset the English musical establishment. He removed to the USA and died in South Africa, without truly realising his full potential. Probably the best performance of the Faust Overture was recorded by Albert Coates but it has never been issued on LP or CD. It exists as a recording in the British Library’s National Sound Archive.” Coates’s grand-daughter Elizabeth Wallfisch is coming to Canberra this month to participate in the Canberra International Music Festival. Albert Coates was the first person to record Bach’s B Minor Mass, which Wallfisch will perform in Canberra.

The other forgotten conductor Brown hopes to have given some historical justice to is the Russian born Englishman, Albert Coates (1882-1953), who was a great favourite of the Tsar. Coates came to England some years after the revolution and he created a sensation at Covent Garden. HMV records recognised his talent. “Only excerpts of his performances were recorded but some of these selections show what a prodigious and volcanic conductor he was. Coates’s volatile personality upset the English musical establishment. He removed to the USA and died in South Africa, without truly realising his full potential. Probably the best performance of the Faust Overture was recorded by Albert Coates but it has never been issued on LP or CD. It exists as a recording in the British Library’s National Sound Archive.” Coates’s grand-daughter Elizabeth Wallfisch is coming to Canberra this month to participate in the Canberra International Music Festival. Albert Coates was the first person to record Bach’s B Minor Mass, which Wallfisch will perform in Canberra.

Brown hopes that contemporary Wagner conductors will consult his book and study statistical evidence in an appendix that provides a meticulous comparison of timing of historical performances to show how performance practice has changed from Wagner’s day. The author explains: “When you look at the historical material, perhaps things today aren’t as they should be in the light of what Wagner wanted. There are three major areas:

Wagner today is performed too slowly. Wagner saw his music as drama, and during Parsifal which is often seen as a most drawn out work, in rehearsal he often called out, ‘Faster! Faster! The people will be bored!’ The Siegfried Idyll was rehearsed by Hans Richter and conducted first by Wagner on Christmas day 1870. Richter performed it later in London and it was timed at 14 ½ minutes – it often comes in now at 20 minutes. You cannot say the performance today reflects the composer’s intentions.

Wagner today is performed too slowly. Wagner saw his music as drama, and during Parsifal which is often seen as a most drawn out work, in rehearsal he often called out, ‘Faster! Faster! The people will be bored!’ The Siegfried Idyll was rehearsed by Hans Richter and conducted first by Wagner on Christmas day 1870. Richter performed it later in London and it was timed at 14 ½ minutes – it often comes in now at 20 minutes. You cannot say the performance today reflects the composer’s intentions. - Today Wagner is performed too loudly. His music is glorious and people love it, but that’s no reason why it should be so loud. Wagner declared that the orchestra should support singers as the sea does a boat: rocking, but never swamping them.

- Modern Wagner is too unvaried in performance. One glorious moment after another is missed in keeping the whole thing in the same tempo, accent and rhythm. Early conductors comment on the variety they were able to create in the orchestra without swamping the singer. The orchestra needs to be exceptionally responsive to the needs of the singers. Wagner wanted a sound that was really an organic texture and a mood as distinct from the current obsession of distinguishing individual instrumental voices.

So, if Brown could meet any of the conductors included in his pantheon, who would he most like to spend time with? “Anton Seidl! There is no question. In Seidl's performances, he used the notes in the score like a great orator, delivering them for their message – it is not blind faithfulness to the text, it is a question of dynamics, speed and so forth, and some of his performances left people absolutely breathless in a way that it’s difficult to imagine today. When Anton Seidl died tragically at the age of 48 he was a cult figure, with 12,000 applications for his funeral, only 4,000 could be accepted. Broadway was congested for seven blocks with people paying homage. He conducted Sunday afternoon concerts down in Brooklyn and he was adored. He had long hair, was very self effacing, rarely smiled and lived for the music.”

So, if Brown could meet any of the conductors included in his pantheon, who would he most like to spend time with? “Anton Seidl! There is no question. In Seidl's performances, he used the notes in the score like a great orator, delivering them for their message – it is not blind faithfulness to the text, it is a question of dynamics, speed and so forth, and some of his performances left people absolutely breathless in a way that it’s difficult to imagine today. When Anton Seidl died tragically at the age of 48 he was a cult figure, with 12,000 applications for his funeral, only 4,000 could be accepted. Broadway was congested for seven blocks with people paying homage. He conducted Sunday afternoon concerts down in Brooklyn and he was adored. He had long hair, was very self effacing, rarely smiled and lived for the music.”

Brown’s passionate, informative authorial guidance invites the discerning music lover to immerse themselves in the vivid evocations of Wagner’s finest interpreters.

Great Wagner Conductors is available in Canberra at the Electric Shadows Bookshop, the Paperchain Bookstore, the National Film and Sound Archives shop, the National Library of Australia shop, the Portrait Gallery Store, and the National Gallery Shop. In Sydney it is available from Berkelouw Books and in Melbourne at Thomas’ Music – among other places.